Forgotten Frames: Slide by slide, a family rediscovers an archive of Antarctic memories

Twin brothers Jeremy and Elliot Warren remember their father, Art Warren, sharing photos of his work with their elementary school classes.

Flipping through his film slides from his days as a physicist, he’d pause before the last one and tell the class that, as a father, he had to end with one of his three beloved sons.

Instead, he’d flip to a photo of a penguin.

In 1958, scientists from 67 countries turned their efforts toward the International Geophysical Year, a project to advance global understanding of the Earth sciences. Art was among them.

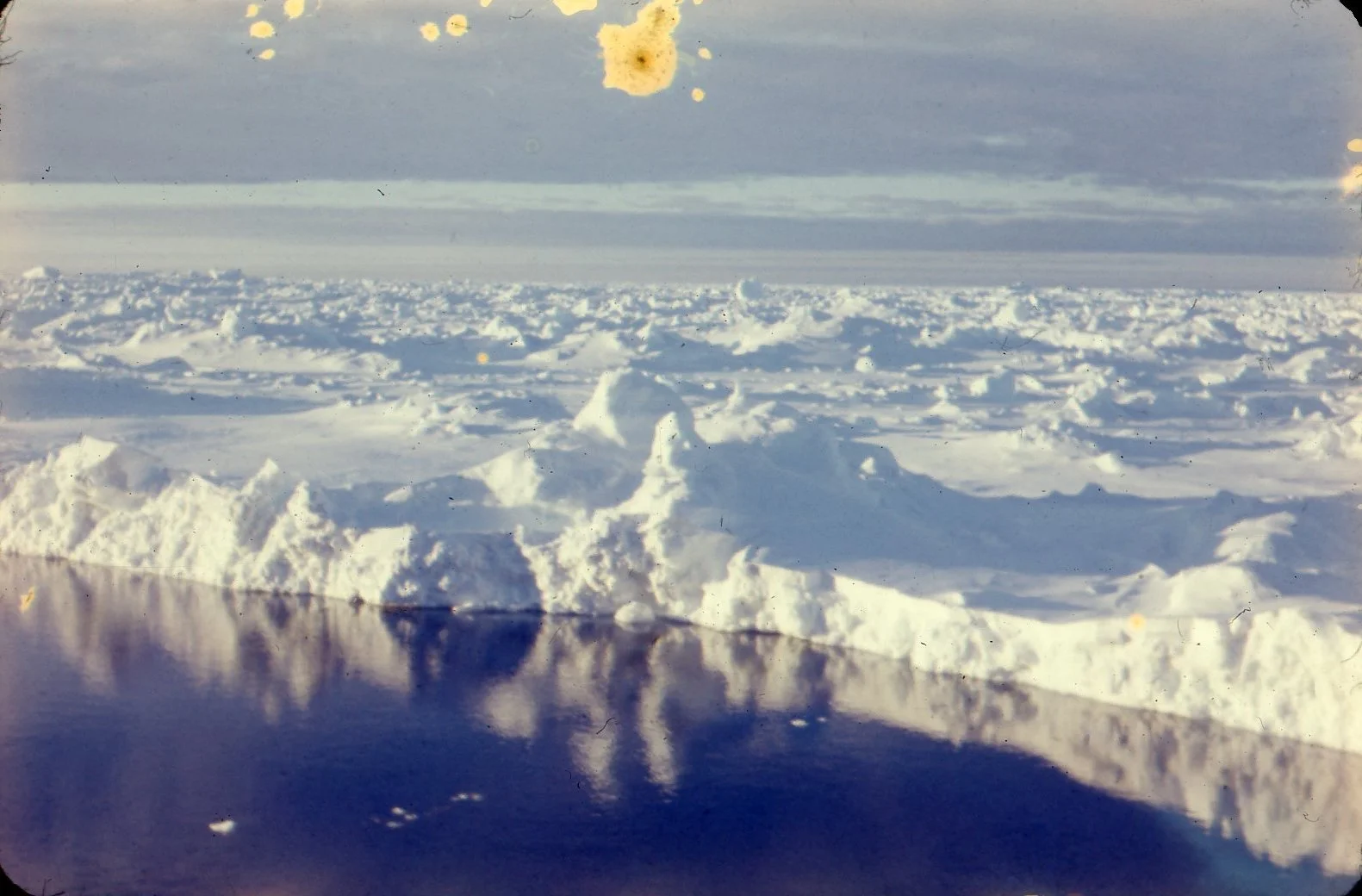

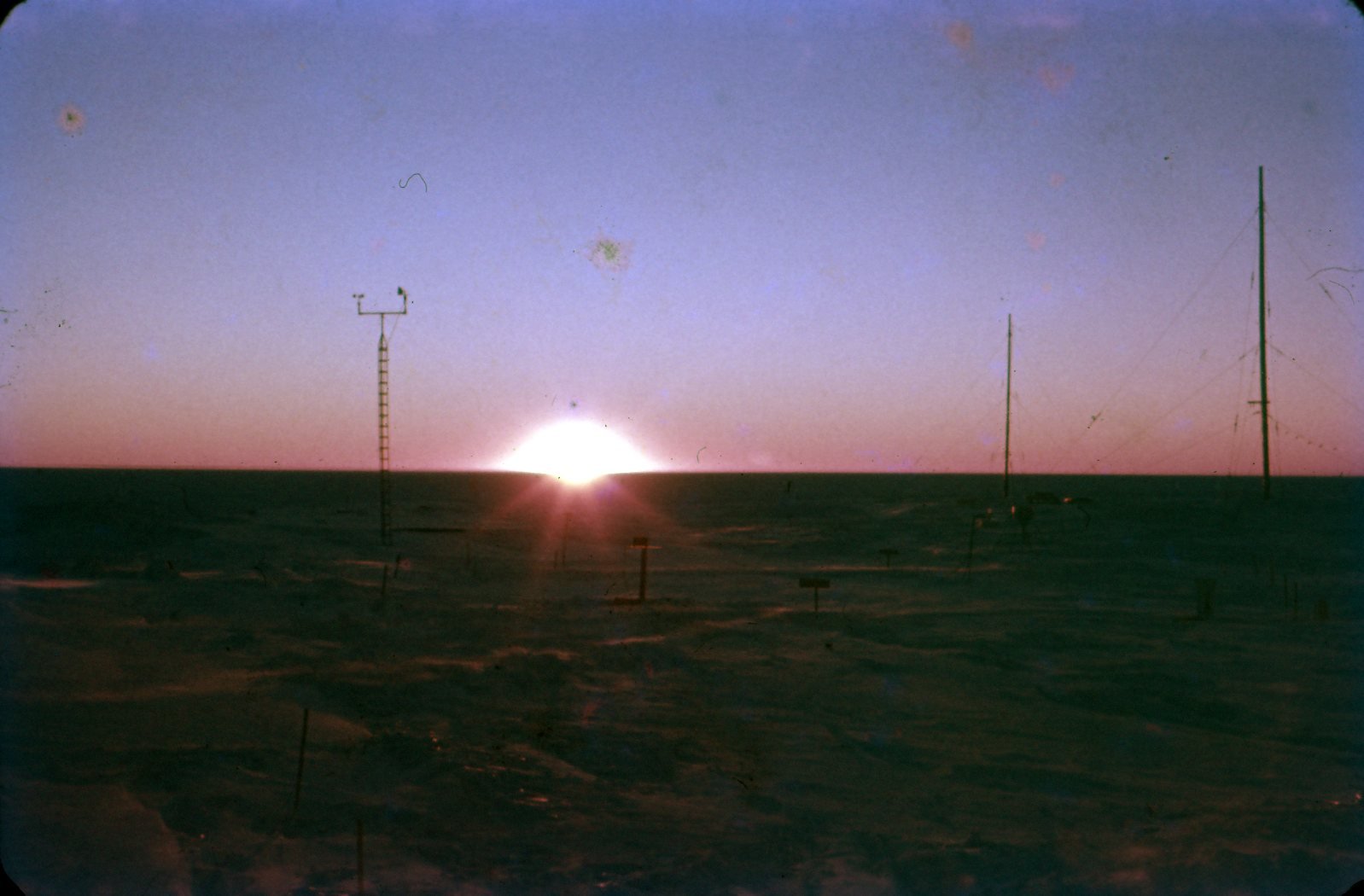

At 25, shortly after earning his Master of Physics at UCLA, he set sail for Antarctica to study the aurora australis, the Southern Lights.

Though he’d never had any interest in the military, he was joining a rowdy Navy crew as the only Jewish sailor. His crewmates suspected, but Art hid his background for the entire year-long assignment due to the prevalence of antisemitism following World War II and throughout the McCarthy era.

For most, this would be the experience of a lifetime. But for Art, born to European immigrants during the Great Depression, it was especially spectacular.

“A lot of what he liked to talk about wasn’t being in Antarctica, but the trip to Antarctica,” Elliot said. “He didn’t grow up going on vacations. His one time going anywhere was moving from New York to LA.” The voyage included stops in several countries, including Argentina, South Africa, and Senegal.

Johannesburg, South Africa, as seen by Art during a shore excursion.

Art’s work required extensive imaging. He applied what he was learning about lenses and light to his personal photography, documenting the trip with his camera.

Some of those photos, and many from that Antarctic voyage, are “famous” in the Warren family, said Art’s grandson, Elias Warren. Others had been tucked away for decades, until Marlo Warren, Art’s widow and stepmother to Jeremy, Elliot, and their brother David, rediscovered and passed them on in October.

“I’m like the first person to look at them in 50 years,” Elliot said about the slides depicting Art’s life in Boston. “I talked about digitizing them a while ago, but never did it. I have bags and bags and bags of slides, mainly of family.”

The crew celebrated crossing the equator with a party, the details of which Art refused to divulge.

Elliot, who has read his father’s diary entries from that time, said Art described the day-to-day work as uneventful.

“He writes mostly about how little he had to do. He worked with equipment and then read,” Elliot said. “It was pure science, but it wasn’t sexy science. It was a lot of math and observation, and maintaining data.”

But it wasn’t all work. In the summer, the crew went on excursions, hiking single-file and leaping over icy crevasses with little visibility. They drank year-round, but in the winter, the temperature could get so low that beers stored outside turned to a cheese-like texture, the alcohol separating from the malts. The crew, undeterred, would mix this freeze-distilled alcohol with their odd assortment of sodas, most often grape.

Jeremy and Elias, who live in San Diego, have begun digitizing their share of the collection with Safelight Labs. Jeremy is looking forward to seeing many more old memories resurface as he and his brothers go through the rest of the photo collection, many of which they haven’t seen since high school.

“We were children being told these stories, not in the way one would tell an adult,” Elliot said. The details, he explained, are blurry.

Perhaps that blurriness is a result of Art’s tendency to stretch the truth. Jeremy put it this way: “He had the gift of gab.”

That gift made Art a prolific storyteller. His loved ones compared wildly different versions of the yarns he wove about his travels.

Not every story was lighthearted. Elliot remembers Art telling him about being in a helicopter that lost power and landed hard, injuring several of the crew. Though he doesn’t remember exactly what happened, he remembers the vivid emotion Art imparted with his storytelling.

“It was one of the scariest things he had ever experienced in his life.”

When he returned to the U.S., Art became active in the anti-war and Civil Rights movements of the 1960s. He was an engineer at McDonnell Douglas but grew to oppose contributing to the Vietnam War.

His commitment to the social issues of the time, coupled with his ability to captivate with his stories, led him down a new path. In 1971, while working at a meatpacking plant in downtown L.A., Art began attending night school at Loyola Law.

As a lawyer, Art made it his mission to fight for the underdog, often representing indigent defendants, injured workers, and the wrongfully convicted. He eventually found his specialty in criminal defense.

“The element of being a champion for justice was a big thing for him,” Elliot said.

When Art died in 2020, he left behind hundreds of photos. Two generations of family milestones are preserved on film, along with his trip to Antarctica, evidence of the incredible stories he told. The photos were developed onto projector slides, meant to be shared and talked over, used to entertain and awe.

Art’s sons, Jeremy and Elliot, are seeing the stories they remember from childhood come to life through their father’s eyes. Elias is looking through photos of his grandfather–the same age as he is now–finding his footing in adulthood in an icy landscape continents away.

What’s to come is even more exciting. The Warrens are looking forward to digging deeper into the remaining bags of photos and excavating even more treasures. What they’ve seen so far is just the tip of the iceberg.